janvier 2022

L’urbanisme de crise. Un nouvel horizon pour les villes et les territoires ?

Coping with COVID-19

in the high-rise, high-density context

Lessons from Singapore’s public housing

Coping with COVID-19 in the high-rise, high-density context : lessons from Singapore’s public housing,

Riurba no

13, janvier 2022.

URL : https://www.riurba.review/article/13-crise/singapore/

Article publié le 1er nov. 2023

- Résumé

- Abstract

Faire face au COVID-19 dans un contexte de grande hauteur et de forte densité : leçons tirées des logements publics de Singapour

En tant que ville-État dense et fortement urbanisée, Singapour est particulièrement vulnérable à la pandémie de COVID-19. Environ 80 % des habitants de Singapour vivent dans des logements sociaux. En se concentrant sur l’environnement physique et la gestion des logements sociaux, ainsi que sur les technologies déployées, cet article vise à fournir une vue d’ensemble des avantages des stratégies d’urbanisme et de conception de Singapour qui ont abouti à son environnement physique actuel face au COVID-19, ainsi que des tentatives de Singapour de formuler d’autres stratégies d’urbanisme et de conception qui seront utilisées pour moderniser et transformer notre environnement afin de mieux répondre et gérer les menaces des futures pandémies. L’article tente de faire la lumière sur la manière de planifier et de gérer les villes de grande hauteur et à forte densité pour les rendre plus résistantes face aux pandémies.

As a high-urbanised, dense city-state, Singapore is especially vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic. About 80% of Singapore residents live in public housing estates. By focusing on the physical environment and management of public housing, as well as technologies deployed, this article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the benefits of Singapore’s urban planning and design strategies resulting in its current physical environment in the face of COVID-19, and Singapore’s attempts to formulate other planning and design strategies that will be used to retrofit and transform our environment to better respond and manage the threats of future pandemics. The article hopes to shed light on how to plan and manage high-rise, high-density cities to make them more resilient to pandemics.

post->ID de l’article : 2638 • Résumé fr_FR : 2651 • Résumé en_US : 2647 •

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has a profound impact on cities and urban life. The changes have sparked discussions about how cities should be planned and designed to respond to current and future pandemics. Although there are some articles about COVID-19 in the field of urban design and planning (e.g., Barbarossa, 2020[1]Barbarossa L. (2020). The post pandemic city: Challenges and opportunities for a non-motorized urban environment. An overview of Italian cases, Sustainability, No.12(17), Art. 7172 [online; Honey-Rosés et al., 2020[2]Honey-Rosés J, Anguelovski I, Chireh V et al. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on public space: An early review of the emerging questions – design, perceptions and inequities, Cities & Health, No.1-17 [online; Sharifi & Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020[3]Sharifi A, Khavarian-Garmsir AR. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management, Science of the Total Environment,No.749, 142391 [online), most focus on medical issues such as disease treatment. Few articles look at how urban planning and design strategies respond to COVID-19 in high-rise, high-density urban settings.

Singapore is a multi-ethnic country where 74.2% of the residents are Chinese, 13.7% are Malays, 8.9% are Indians, and 3.2% are from other ethnic groups (Department of Statistics, 2021[4]Department of Statistics. (2021). Population trends 2021. Singapore: Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry [online). It is a city-state with 733 km2 of land, 100% urbanised with a high population density. Its density and limited land resources make Singapore vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic. Singapore’s responses to COVID-19 must be carefully planned to reduce the impact and achieve a balance between population health and economic development.

The situation of COVID-19 in Singapore has gone through ups and downs. With the first imported case confirmed on January 23, 2020, Singapore is one of the first countries outside China to be affected by COVID-19. Local transmission began to develop in February 2020 and progressed to an outbreak of cases in the dormitories of foreign workers. This led to a two-month-long Circuit Breaker[5]“What you can and cannot do during the circuit breaker period” [online starting on April 7, 2020. As the situation got better, from 2 June 2020 to 7 May 2021, a cautious series of re-opening measures were implemented in three phases to resume activities. Because of the rise of the Delta variant, Singapore reverted to Phase 2 in May 2021 and changed back and forth between Phase 2 and Phase 3 till 9 August 2021. As the percentage of vaccinated population increased, Singapore entered its “Preparatory Stage of Transition towards COVID-19 Resilience” on 10 August 2021, which was changed to the “Stabilisation Phase” from 27 September to 21 November 2021 to reduce the transmission rate and relieve the pressure on the healthcare system[6]“Updates On Local Situation and Maintaining the Stabilisation Measures” [online. In January 2022, the rise of the Omicron variant led to a new surge of cases, with the highest daily count of 26,032 cases on 22 February 2022, and the number of cases started to fall since then. From April 26, 2022, major easing of COVID-19 rules has taken effect (e.g., no more requirements for safe distancing) and Singapore is on its way to restoring pre-COVID-19 normalcy.

In Singapore, 78.7% of Singapore residents live in high-rise, high-density public housing developed by the Housing and Development Board (HDB) (Department of Statistics, 2021[7]Op. cit.). High-rise, high-density environment tends to be associated with compact living conditions and crowding (Ng, 2009[8]Ng E. (Ed.). (2009). Designing high-density cities for social and environmental sustainability, London, Earthscan.), which poses challenges to containing the spread of COVID-19. However, articles also indicate that the relationship between density and COVID-19 is inconsistent (Sharifi & Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020[9]Op. cit.). Besides density, other factors such as the promptness of COVID-19 measures and access to healthcare services are also important (Idem). In the case of Singapore, despite the constraints, Singapore’s early response to the pandemic was acknowledged as relatively successful. The COVID-19 fatality rate in Singapore is 0.11%, being one of the lowest in the world[10]Johns Hopkins Coronavirus resource center, Mortality analysis [online.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the benefits of Singapore’s urban planning and design strategies resulting in its current physical environment in the face of COVID-19, and Singapore’s attempts to formulate other planning and design strategies that will be used to retrofit and transform our environment to better respond and manage the threats of future pandemics. It focuses on Singapore’s public housing as it accommodates the majority of Singapore’s population. The following sections will first briefly introduce Singapore’s public housing, then discuss Singapore’s urban planning and design strategies from three dimensions of the physical environment, management, and technology, and finally, conclude with reflections on Singapore’s public housing development in different periods. This article hopes to provide valuable insights on how to plan and design high-rise, high-density cities in a post-pandemic world.

Singapore’s public housing

Since its establishment in 1960, HDB takes a high-rise, high-density development approach and embraced the “British New Town” concept. Until now, HDB has built 24 new towns and 3 estates. Each new town is planned to house 150,000 to 300,000 people, being self-sufficient to the extent of satisfying households’ daily needs and providing a certain number of job opportunities (Tan et al., 1985[11]Tan TK, Tong LC, An TS, Cheong LW, Kwok K. (1985). Physical planning and design, In Wong AK & Yeh SH (Eds.), Housing a nation: 25 years of public housing in Singapore (pp. 56-112), Maruzen Asia for HDB.).

HDB housing development has gone through 5 stages. The first two stages took place in Queenstown and Toa Payoh during Singapore’s housing shortage period with no real planning model applied (Idem). The planning and design were pragmatic and simple with minimal emphasis on amenities and open spaces. In the 1970s, the Neighbourhood Prototype Model marks the third stage of development, with rationalized land use and increased standard of facility provision, especially for recreational and educational facilities (Idem). According to Liu (1975[12]Liu TK. (1975). Design for better living conditions. In Yeh SH (Ed.), Public housing in Singapore: A multi-disciplinary study (pp. 117-184), Singapore, Singapore University Press.), the optimal neighbourhood size is 40 hectares with a 360-meter service radius (designed as a maximum of 400 meters), holding 4000-6000 dwelling units.

In the late 1970s, the concept of “precinct” was introduced to promote a sense of community, bring more varieties to HDB housing estates, and facilitate more detailed design considerations. Together with the New Town Structural Model, the “precinct” concept marks the fourth stage of new town development. Precincts are smaller breakdowns of neighbourhoods, serving 400-800 families living in 4-8 blocks. A precinct is designed to be easily recognised with a clear boundary and a precinct centre towards which all HDB blocks face. Later, an advanced planning model was implemented in towns such as Yishun, Jurong East, and Tampines with a clearer hierarchy of roads and amenities. Different levels of neighbourhood amenities and open spaces are distributed from the town centre to neighbourhood centres and precinct centres. For example, the planning standard for the provision of shops is one shop to 70 dwelling units, with 20% in the town centre, 50% in neighbourhood centres, and 30% in precincts (Fernandez, 2011[13]Fernandez W. (2011). Our homes: 50 years of housing a nation, Singapore, Straits Times Press.; Tan et al., 1985[14]Op. cit.).

Since the 1990s, more efforts have been given to variety and identity to create a total living environment (Fernandez, 2011[15]Op. cit.). In the 2000s, the youngest town Punggol was developed with the vision of “a waterfront town of the 21st century”. It marks the fifth stage of the development of new towns. Due to the global trend of sustainable development, HDB planned to bring more green to the housing estates and strived for “strong and healthy” communities (Idem). Many precincts in Punggol are planned with residential blocks enclosing an elevated open space (eco-deck) with carparks below (Hee, 2017[16]Hee L. (2017). Constructing Singapore public space, Singapore, Springer [DOI).

Physical Environment

During the COVID-19 period, a great number of residents had to work from home and their life mostly revolved around HDB towns. This section will discuss seven dimensions to see how HDB towns respond to COVID-19, including daily amenities and services, healthcare facilities, green space, open space, urban mobility, co-working space, and buildings.

Daily amenities and services

Access to amenities and services is a basic human need and a key indicator of a walkable and healthy living environment. During the COVID-19 period, the idea of providing essential amenities within a 15-minute non-motorised trip, or “15-min city,” has regained popularity around the world (Barbarossa, 2020[17]Op. cit.; Pozoukidou & Chatziyiannaki, 2021[18]Pozoukidou G, Chatziyiannaki Z. (2021). 15‐minute city: Decomposing the new urban planning Eutopia, Sustainability, No.13(2), Art. 928 [online). This vision has nearly been realised in Singapore’s public housing estates, thanks to the character of its high-rise, high-density environment.

In HDB towns, the amenities and services are distributed in different hierarchies from the town centre to neighbourhood centres and precinct centres. A town centre is usually equipped with major commercial services, sports complexes, cinemas, a branch public library, a bus interchange, and a mass rapid transit (MRT) station. A neighbourhood centre is planned with facilities for daily needs, including a hawker centre (a naturally ventilated complex housing many stalls selling affordable food and beverages) and market, coffee shops, shops, clinics, and sports and recreational facilities. Playgrounds, fitness corners, precinct gardens, and basic commercial facilities such as convenience stores, clinics, and coffee shops are located at the precinct centre (Tan et al., 1985[19]Op. cit.).

The amenities and services at different spatial levels in HDB towns allow residents to meet daily needs close to homes and avoid public transport, thereby limiting personal exposure to COVID-19. The accessibility of the physical environment was brought to a new standard in Heng et al.’s (2020[20]Heng CK, Fung JC, Cho IS, Malone-Lee LC. (2020). 未来高密度居住区规划与设计框架研究. 规划师,No.36(21), pp. 35-44 [online) vision of a “One-Minute Street-Based Residential Township.” In the master plan for Dover in Queenstown, Heng et al. (2020[21]Op. cit.) proposed a 1.6 km long central spine as its planning structure to create a human-centric, street-based, mixed-use living environment where major nodes with lifestyle, community and other amenities such as senior activity centres, childcare centres, and eateries are placed at 400 metres intervals along the spine. A secondary node with facilities for daily routines such as coffee shops, bakeries and a clinic is inserted between two major nodes.

The outbreak of pandemics also raises a new focus on creating healthy living environments. In Singapore, using the oldest town Queenstown as a pilot site, HDB in collaboration with the National University of Singapore and the National University Health System, as well as other agencies and partners, have started to conduct research and test initiatives to create a community that promotes residents’ healthy behaviours, productive longevity, intergenerational cohesion, and a safer environment for ageing in place[22]Housing & Development Board, Health District Queenstown [online.

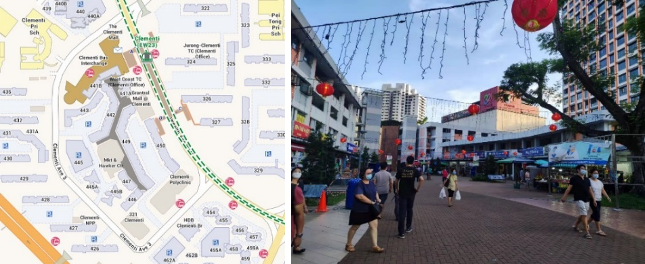

However, a study on the provision of service shops (e.g., food and beverage, groceries) in HDB towns shows that compared to mature towns, newer towns have fewer service shops in total and fewer shops per dwelling unit (Sun, 2013[23]Sun H. (2013). “Social effects of the provision and distribution of daily service shops in HDB new town in Singapore – Using case studies of Bedok, Jurong East, Bishan, Sengkang and Punggol new towns”, Master thesis, National University of Singapore.). The reason for this is partly due to the increasing preference for air-conditioned modern shopping malls, particularly among young generations (Heng & Yeo, 2017[24]Heng CK, Yeo SJ. (2017). Singapore chronicles: Urban planning, Singapore, Institute of Policy Studies and Straits Times Press.). Open-air pedestrian shopping streets can be found in the town centres and neighbourhood centres of the early-generations towns such as Toa Payoh and Clementi (Figure 1). However, the town centres in towns developed after the 1990s, such as Senkang and Punggol, mostly consist of shopping complexes (Figure 2). Compared to open-air shopping streets, concentrating amenities and services in one large, privately-owned shopping mall may hamper the accessibility and affordability of amenities and services. Besides, the outbreak of COVID-19 highlights the need to reflect on the shopping trend since the preference for neighbourhood shops may increase as people do not need to use public transport and have lower risks of infection as compared with the air-conditioned shopping malls (Hong & Choi, 2021[25]Hong S, Choi SH. (2021). “The urban characteristics of high economic resilient neighborhoods during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case of Suwon, South Korea”, Sustainability, No. 13(9), Article 4679 [online). A study also finds that proximity to numerous local facilities is associated with better health and well-being during the COVID-19 period (Mouratidis & Yiannakou, 2021[26]Mouratidis K, Yiannakou A. (2021). “COVID-19 and urban planning: Built environment, health, and well-being in Greek cities before and during the pandemic”, Cities, No. 121, Art. 103491 [online).

Healthcare facilities

Singapore’s healthcare delivery system has an island network of outpatient polyclinics and general practitioner (GP) clinics to provide primary healthcare services. Those who need further treatment will be referred to hospital care consisting of inpatient, outpatient, and emergency services. This two-level system decentralises healthcare facilities and helps alleviate the burden on public hospitals.

Within easy walking distance in earlier generations towns, GPs are usually located together with commercial shops in the precinct centres, neighbourhood centres, and town centres. On February 18, 2020, about 900 GPs were reactivated as Public Health Preparedness Clinics (PHPCs) to diagnose and manage COVID-19 infections and provide subsidised treatment and medicines (Chang & Yong, 2020[27]Chang N, Yong M. (2020, February 14). Public Health Preparedness Clinics reactivated to reduce risk of COVID-19 spread, Channel NewsAsia [online). PHPCs are trained to know the proper care procedures for each patient based on the assessed risk and diagnosis, and they would refer patients who are suspected of having pneumonia to hospitals for additional testing and treatment. The Swab & Send Home programme is also offered by PHPCs to provide government-funded swabs for eligible patients.

Communal facilities and open spaces in HDB towns are also adapted to provide healthcare services during the COVID-19 period. Community Clubs (CCs) are common spaces consisting of various facilities for people of all races to meet, socialise and promote social bonding. There are 108 CCs in Singapore, each serving about 15,000 households. To respond to COVID-19, CCs suspended activities involving group gatherings and were activated as vaccination centres, as well as collection centres for free masks, hand sanitisers, Antigen Rapid Test self-test kits, and TraceTogether tokens (for contact tracing purposes).

Void decks are vacant spaces on the ground floor of housing blocks and towers. Since the 1970s, they have been constructed in HDB estates to provide common spaces for residents to meet and interact. They can accommodate various temporary and permanent programmes (e.g., chess corners, residents’ committees, wedding celebrations) and meet future needs (Tan et al., 1985[28]Op. cit.). During the Covid-19 period, when multiple cases were identified at several HDB blocks, void decks were used for conducting mandatory COVID-19 testing for the residents to identify community infection cases (Chia, 2021[29]Chia O. (2021, July 29). “Mandatory Covid-19 testing for residents of 2 HDB blocks in Choa Chu Kang and Jurong West”, The Straits Times [online). However, in newer towns where HDB blocks have more complex plans resulting in smaller void decks, precinct pavilions are built to cater to such needs.

Green space

As indoor activities are largely restricted during the COVID-19 period, there has been a boom in the use of parks and green spaces in different countries worldwide (Honey-Rosés et al., 2020[30]Op. cit.; Lu et al., 2021[31]Lu Y, Zhao J, Wu X, Lo SM. (2021). “Escaping to nature during a pandemic: A natural experiment in Asian cities during the COVID-19 pandemic with big social media data”, Science of the Total Environment, No. 777, Art. 146092 [online). In Singapore, even during the lock-down, residents are still allowed to exercise in green spaces. Although available studies examining the impact of green spaces on mental well-being during the COVID-19 period show inconsistent results (Mouratidis & Yiannakou, 2021[32]Op. cit.; Olszewska-Guizzo et al., 2021[33]Olszewska-Guizzo A, Fogel A, Escoffier N, Ho R. (2021). “Effects of COVID-19-related stay-at-home order on neuropsychophysiological response to urban spaces: Beneficial role of exposure to nature?”, Journal of Environmental Psychology, No. 75, Art. 101590 [online; Wortzel et al., 2021[34]Wortzel JD, Wiebe DJ, DiDomenico GE, Visoki E et al. (2021). “Association between urban greenspace and mental wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic in a U.S. cohort”, Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, No. 3 [online), green spaces are generally considered as providing a sense of relief from spatial isolation and a refuge from the stress of lock-down.

There are different categories of parks and green spaces in HDB towns, ranging from town parks to neighbourhood parks, precinct gardens, pocket green spaces, and park connector networks (i.e., a network of walking and cycling paths connecting parks and green spaces). As early generations of HDB towns such as Queenstown and Toa Payoh were developed during a period of severe housing shortage, the provision and design of green spaces received little attention. The early generations of HDB blocks were built with a south-north orientation with incidental or residual open spaces (Figure 3a). By contrast, greater emphasis was given to green spaces in newer towns. For example, one precinct in Bukit Panjang completed in 1999 has a precinct garden with lush greenery, playgrounds, fitness corners, and a man-made stream lined with rocks (Figure 3b). In Punggol, a 4.2km man-made waterway was constructed, which meanders through the entire town of Punggol and provides opportunities for waterfront recreational activities.

Urban green spaces are beneficial for population health and wellbeing (Lee et al., 2015[35]Lee AC, Jordan HC, Horsley J. (2015). “Value of urban green spaces in promoting healthy living and wellbeing: Prospects for planning”, Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, No. 8, p. 131-137 [online). They have environmental benefits, such as counteracting the urban heat island effect and minimising air and noise pollution; they can also benefit physical and mental well-being by encouraging physical activities and social interactions and reducing stress and anxiety (Idem). The Singapore Green Plan 2030[36]Cf. Green Plan, Key focus areas [online unveiled on 10 February 2021 pushes Singapore’s current green space provision to a new standard. By 2030, Singapore aims to increase the land area of nature parks by more than 50% from the 2020 baseline and have every household live within a 10-minute walk of a park. In addition, 30 therapeutic gardens will be established across Singapore.

Due to transport restrictions and border control measures, COVID-19 has disrupted food supply chains and called attention to the importance of local food production and self-sufficiency (Sharifi & Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020[37]Op. cit.). This is a particular challenge for Singapore due to its limited land and natural resources. To enhance food security, Singapore aims to increase self-production by 300% by 2030, with locally produced food meeting 30 per cent of the country’s nutritional needs (Teng, 2020[38]Teng P. (2020). “Assuring food security in Singapore, a small island state facing COVID-19”, Food Security, No. 12(4), p. 801-804 [online). This will involve using land more innovatively and effectively for commercial farming, such as deploying underutilised spaces (e.g., HDB multi-storey carpark rooftops) and creating new building typologies. The number of community gardens in Singapore had increased since the launch of the nationwide gardening campaign – Community in Bloom in 2005, which can also promote community bonding and population health (Lovell et al., 2014[39]Lovell R, Husk K, Bethel A, Garside R. (2014). “What are the health and well-being impacts of community gardening for adults and children: A mixed method systematic review protocol”, Environmental Evidence, No. 3(1), p. 20 [online).

Open space

Open spaces as communal and social spaces are important for a sense of community and residents’ well-being (Francis et al., 2012[40]Francis J, Giles-Corti B, Wood L, Knuiman M. (2012). “Creating sense of community: The role of public space”, Journal of Environmental Psychology, No. 32(4), p. 401-409 [online].). Open spaces in HDB towns can be found at different spatial hierarchies, and many of them are located next to the commercial shops in the neighbourhood centre and town centre. As a high-rise, high-density city with high population density, one of the challenges is managing social distancing in open spaces. Singapore facilitates the management by using tapes and temporary fences to indicate where to sit, stand, enter and exit (Figure 4).

The social distancing rules during the COVID-19 period greatly affect the utilisation of open spaces and public life (Honey-Rosés et al., 2020[41]Op. cit.). Some people are afraid of going out and contacting others, which reduces opportunities for socialising. The COVID-19 pandemic is associated with loneliness in the general adult population, and loneliness is strongly linked to mental illness (Pai & Vella, 2021[42]Pai N, Vella SL. (2021). “COVID-19 and loneliness: A rapid systematic review”, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, No. 55(12), p. 1144-1156 [online). This is more serious for older adults living alone, especially considering that their regular group activities organised by communal and eldercare institutions (e.g., senior activity centres, residents’ committees) have been suspended. A balance between social interaction and social distancing could be sought, such as by designing street furniture that makes social distancing easier to maintain (Askarizad & He, 2022[43]Askarizad R, He J. (2022). “Post-pandemic urban design: The equilibrium between social distancing and social interactions within the built environment”, Cities, No. 124, Art. 103618 [online).

The outbreak of COVID-19 also calls attention to the value of large flexible spaces as they could be used for public health purposes (Honey-Rosés et al., 2020[44]Op. cit.). The availability of open spaces that could be easily adapted for emergency health purposes is a key feature of a resilient city. For example, to complement the efforts of the PHPCs, former schools and outdoor bus interchanges have been converted to carry out COVID-19 swab tests. The large exhibition halls of the Singapore Expo were repurposed into a facility that could provide care for COVID-19 patients (Centre for Liveable Cities, 2021[45]Centre for Liveable Cities. (2021). Singapore’s COVID-19 response and rethinking the new urban normal: A commentary. Singapore: Centre for Liveable Cities [online).

Urban mobility

Evidence shows that travel restrictions during the COVID-19 period considerably lowered NO2 and CO, which are pollutants directly associated with transport (Sharifi & Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020[46]Op. cit.). Together with the concerns for climate change and leading healthy lifestyles, redesigning streets to provide more space for active transport, such as walking and cycling, has gained popularity. Closing roads for pedestrians and cyclists have been temporarily applied in some cities such as Boston (Honey-Rosés et al., 2020[47]Op. cit.).

The outbreak of COVID-19 was also found to be linked to reduced interest in taking public transport due to due to the risks of infection (Barbarossa, 2020[48]Op. cit.; Bracarense & Oliveira, 2021[49]Bracarense LD, Oliveira RL. (2021). “Access to urban activities during the Covid-19 pandemic and impacts on urban mobility: The Brazilian context”, Transport Policy, No. 110, p. 98-111 [online). In Singapore, the high cost of owning a car makes private motorised transport an unlikely option for most public transport users. To reduce travel time and make public transport more accessible, Singapore aims to achieve the vision of a “45-Minute City with 20-Minute Towns” by 2040 by expanding rail networks, improving bus speeds, and bringing jobs closer to homes (Land Transport Authority[50]Land Transport Authority. Land Transport Master Plan 2040. Singapore: Land Transport Authority [online). This means that by using Walk-Cycle-Ride modes of transport, 9 out of 10 trips made during peak hours will be completed in less than 45 minutes while all trips to the nearest neighbourhood centre will take less than 20 minutes.

COVID-19 also underlines the benefits of cycling (Barbarossa, 2020[51]Op. cit.; Nikitas et al., 2021[52]Nikitas A, Tsigdinos S, Karolemeas C, Kourmpa E, Bakogiannis E. (2021). “Cycling in the era of covid-19: Lessons learnt and best practice policy recommendations for a more bike-centric future”, Sustainability, No. 13(9), Art. 4620 [online), which is not only beneficial to physical health but also a travel mode that is easy to comply with safe distancing measures. Singapore has already built more than 440 km of cycling paths and aims to expand the cycling path network to more than 1,000 km by 2030[53] Land Transport Authority, “Cycling” [online. Singapore has cycling path networks in nine HDB towns such as Ang Mo Kio and Tampines and will be building more in six towns to facilitate intra-town travel as well as connect residents from their homes to MRT stations, bus interchanges, and other amenities nearby and promote active and healthy lifestyles[54] Op. cit..

Co-working space

During the COVID-19 period, working from home is the default working mode for quite a long period in Singapore. One problem with such a work arrangement is to separate work from personal life, and co-working spaces would be a solution. Before the outbreak of COVID-19, most co-working spaces in Singapore were located in the central region which demands high rental fees. The outbreak of COVID-19 not only accelerates the trend of working from home but also hastens the decentralisation of co-working spaces (Foo, 2021[55]Foo ST. (2021, June 24). “Reimagining the workspace of tomorrow”, The Business Times [online). The decentralisation implies more affordable co-working spaces close to homes as well as lower risks of contracting COVID-19.

Working from or near home also affects other aspects of everyday life. For example, it reduces the need to commute, thereby mitigating the problems of environmental pollution and traffic congestion during peak hours. People who work from or near home are also more likely to eat near home, send their children to childcare or schools near home, use the amenities and socialise near home, and have the chance of visiting parents who use nearby daycare services during mealtimes. Therefore, embedding co-working spaces within a neighbourhood could help promote the economic and social sustainability of the neighbourhood.

Buildings

The outbreak of COVID-19 provides an opportunity for rethinking building design to prepare for future epidemics. For example, discussions have been raised on how to redesign building entrances to facilitate temperature monitoring, contact tracing and reduce human contacts, such as introducing automated entry and exit points and contactless infrastructure for facial recognition. Future residential buildings could also be designed to facilitate non-intrusive wastewater surveillance as the method is found useful for detecting COVID-19 cases (Wong et al., 2021[56]Wong JC, Tan J, Lim YX et al. (2021). “Non-intrusive wastewater surveillance for monitoring of a residential building for COVID-19 cases”, Science of the Total Environment, No. 786, Art. 147419 [online). Singapore has implemented wastewater surveillance in HDB buildings, dormitories, and student hostels (Ng, 2021[57]Ng KG. (2021, July 8). “S’pore to double Covid-19 wastewater testing surveillance sites by 2022 from current 200”, The Straits Times [online). Once viral fragments are found in the building’s wastewater, residents will be required to take swab tests to identify the infected cases.

Another important aspect is the building layout. HDB blocks are designed to promote cross-ventilation to reduce the reliance on mechanical cooling from electric fans and air conditioners. The lift lobbies of HDB blocks are naturally ventilated at all levels and especially at the first storey due to the provision of void decks, which improve wind flow in the precinct. In HDB’s first eco-precinct – Treelodge @ Punggol – all residential blocks were wind-tunnel tested, with windows facing north-south to encourage natural ventilation and indoor air quality (Lau et al., 2010[58]Lau JM, Teh PS, Toh W. (2010). “HDB’s next generation of eco-districts at Punggol and eco-modernisation of existing towns”, The IES Journal Part A: Civil & Structural Engineering, No. 3(3), p. 203-209 [online). Besides, the Stay-Home measures also lead to discussions about how to design dwelling units to accommodate living as well as working and learning, such as making internal walls removable to allow flexible layouts (Centre for Liveable Cities, 2021[59]Op. cit.).

Management

Besides physical environment, management plays an important role in containing the spread of COVID-19. Management can facilitate long-term visioning and make cities better prepared for public health crises. One good example in Singapore is the development and management of PHPC clinics, which are lessons learned from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and H1N1 pandemics. Besides improving pandemic preparedness, management also helps to contain the spread of COVID-19 by affecting people’s behaviours.

Different from physical environment that is hard to change, management can easily affect how people use amenities and facilities. In Singapore, different safety management measures are implemented based on the COVID-19 situation to strike a balance between population safety and the resumption of economic and social activities. For example, according to Phase 2 measures[60]“Return to Phase 2 (Heightened Alert) Measures” [online, group sizes of up to 2 persons are allowed for social gatherings; dine-in at all food and beverage establishments are ceased with only takeaway and delivery options allowed, all strenuous indoor exercise classes are ceased; mask-off personalised services (e.g. make-up services) are not allowed except for medical and dental consultations; and entertainment venues (e.g., bars, karaoke outlets) that require many people to be in close proximity for lengthy periods of time are closed.

By contrast, COVID-19 measures in Phase 3 are eased to allow more social and economic activities[61]“Updates on Phase 3 (Heightened Alert) Measures” [online, particularly for those who are fully vaccinated. For instance, group sizes of up to 5 persons are allowed for social gatherings, dine-in, indoor high-intensity mask-off sports and exercise activities if any individual in the group is fully vaccinated, a recovered patient, or has a valid COVID-19 test result. If not eligible, group sizes of 2 persons are allowed for the above-mentioned activities. Mask-off personalised services are allowed while entertainment venues such as karaoke outlets are still closed.

Contact tracing is an important public health measure in Singapore to identify close contacts of COVID-19 patients who can then be quarantined or monitored closely to contain the spread of the virus. To facilitate contact tracing, SafeEntry check-in, or scanning a SafeEntry QR code with a phone camera, was required at places with a higher risk of non-transient contacts, such as schools, supermarkets, workplaces, shopping malls, and dine-in food and beverage establishments. This was later replaced by the TraceTogether app or token to increase convenience (Li, 2021[62]Li X. (2021, September 26). “Are certain neighbourhoods more prone to being struck by Covid-19?”, The Straits Times [online). As hawker centres and markets are naturally ventilated buildings opened on all sides, temporary fencing was put up to facilitate vaccination-differentiated measures. Stickers with different colours are distributed and collected at entrances and exits to identify vaccinated individuals and manage the crowd.

The implementation of social distancing measures also requires proper management. In Singapore, from 27 March 2020 till 25 April 2022, it is considered an offence to deliberately sits within one meter of others in a public place or on a fixed seat marked as not to be occupied or waits in line within one meter of another person. It is hard to enforce social distancing in a high-density city like Singapore (Liu et al., 2020[63]Liu V, Diman H, Lim J. (2020, March 22). “Coronavirus: Social distancing starts – from malls to supermarkets”, The Straits Times [online), such as when taking public transport during peak hours. In this case, other measures are required. For example, during the COVID-19 period, no talking is allowed on public transport in Singapore to prevent droplets from spreading and reduce risks (Toh, 2021[64]Toh TW. (2021, May 14). “Possible to keep public transport ‘very safe’ with Covid-19 precautions: Ong Ye Kung”, The Straits Times [online).

Technology

Technology provides new ways for people to meet daily needs and facilitate management. In terms of daily necessary activities, digital services such as Zoom is widely used for working and learning from home. To reduce human contact, e-payments have been widely adopted by food and beverage establishments, many of whom still adopt cash payments before the outbreak of COVID-19. The demand for e-commerce and delivery services has also increased, although the shift toward e-commerce may challenge the viability of brick and mortar stores (Bitterman & Hess, 2021[65]Bitterman A, Hess DB. (2021). “Going dark: The post-pandemic transformation of the metropolitan retail landscape”, Town Planning Review, No. 92(3), p. 385-393 [online). Besides, the COVID-19 pandemic leads to an increased demand for telemedicine (Ahmed et al., 2020[66]Ahmed S, Sanghvi K, Yeo D. (2020). “Telemedicine takes centre stage during COVID-19 pandemic”, BMJ Innovations, No. 6(4), p. 252 [online). In Singapore, as the number of cases increased with most residents getting fully vaccinated and COVID-19 symptoms getting milder, many patients started to recover from home and use telemedicine. Several GPs have started to provide telemedicine services to ease the load of telemedicine providers (Tan, 2021[67]Tan C. (2021, September 30). “S’pore GPs stepping up to provide telemedicine care for Covid-19 patients on home recovery”, The Straits Times [online). Some of these trends would have implications for urban planning and design in a post-pandemic future, and their impacts on urban forms and human behaviours need to be further investigated.

Technology is also useful in public health regulation and administration to respond to COVID-19. For example, contact tracing, facilitated by apps such as TraceTogether, has enabled the government to identify, isolate, and quarantine close contacts of COVID-19 patients more accurately and promptly. To manage the crowd, digital platforms have been developed to track crowd levels. For example, the National Parks Board developed an interactive webpage to track population density in parks in real time[68]This website. Similarly, the Urban Redevelopment Authority developed Space Out[69]This website to provide regular updates on the crowd levels in parks, supermarkets, malls, and sports and recreational facilities in Singapore. These digital platforms assist the public in making more informed decisions on where to go and when to buy necessities.

Another important contribution of technology is to facilitate social interaction and relieve stress and isolation by offering online social activities, such as group exercises and social gatherings. During the COVID-19 period, people tend to have fewer social activities because of movement restrictions, social distancing, and the suspension of non-essential services. Older people, especially those living alone, are at a higher risk of depression and isolation. When eldercare centres were closed due to COVID-19 measures, to address the loneliness and safety issues of older people, staff started to make video and phone calls to check in with them or visit their homes if they failed to respond (Nanda, 2021[70]Nanda A. (2021, October 9). “Seniors stuck at home, caught between loneliness and fear of Covid-19”, The Straits Times [online). Government agencies have also started to assist older people to learn basic digital skills (Yip et al., 2021[71]Yip W, Ge L, Ho AH, Heng BH, Tan WS. (2021). “Building community resilience beyond COVID-19: The Singapore way”, The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, No. 7, Art. 100091 [online). Singapore’s dense residential environment and shorter travel distance help to make such visits less onerous.

Debate: Are newer towns better?

This article has discussed various aspects that made Singapore’s responses to COVID-19 relatively successful. The high-rise high density physical environment of HDB towns provides more green and open spaces, essential amenities and services near residents’ homes; management helps Singapore better prepared for pandemics and facilitates the implementation of COVID-19 measures; technology provides alternatives for the residents to meet daily needs and enables more efficient and timely management.

The physical environment of different generations of HDB towns in Singapore differs in the distribution of amenities and services, residential block typologies and spatial configuration of void decks, the provision of parks and green spaces, and aesthetics. Newer towns give more emphasis on the design of residential blocks and green spaces, with shopping complexes and smaller void decks. By contrast, mature towns have more ground-floor shops and simpler and larger void decks. Considering the trend of HDB town development, two questions are raised: (1) which generations of HDB towns are more vulnerable to COVID-19? (2) Are towns that are less vulnerable to COVID-19 better for population health in the long run?

The vulnerability of different towns to COVID-19 is associated with social and physical environmental features (Chin & Bouffanais, 2020[72]Chin WC, Bouffanais R. (2020). “Spatial super-spreaders and super-susceptibles in human movement networks”, Sci Rep, No. 10(1), Art. 18642 [online; Leong et al., 2021[73]Leong CH, Chin WC, Feng CC, Wang YC. (2021). “A socio-ecological perspective on COVID-19 spatiotemporal integrated vulnerability in Singapore”. In Shaw SL, Sui D (Eds.), Mapping COVID-19 in space and time: Understanding the spatial and temporal dynamics of a global pandemic, Springer International Publishing, p. 81-111.). Neighbourhoods that are more densely populated, with higher proportions of young and elderly residents, lower socioeconomic conditions (e.g., lower housing resale prices), more proximity to places linked to COVID-19 infections (e.g., hawker centres, wet markets, shopping malls), more diverse land use, and more intense population activity (i.e., a larger number of commuters passing through) tend to be more vulnerable to COVID-19 (Leong et al., 2021[74]Op. cit.). For example, the vulnerability of the identified two neighbourhoods in Toa Payoh can be explained by the greater proportion of older blue-collar residents who are unable to work from home, rely on public transport, and have to be in contact with many people due to the nature of their jobs (Idem). People of lower socioeconomic status are generally more vulnerable to pandemics because they are more likely to have more exposure to risks and limited access to resources and services (Sharifi & Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020[75]Op. cit.; Wade, 2020[76]Wade L. (2020). “An unequal blow”, Science, No. 368(6492), p. 700-703 [online).

Besides socio-economic factors, the correlation between physical environmental factors with spatial vulnerability highlights a dilemma because, on the one hand, places with more diverse land use and closer proximity to amenities and services tend to promote healthy behaviours such as walking and promote environmental, social, and economic sustainability in the long run (Hwang, 2017[77]Hwang E. (2017). “Impacts of objective neighborhood built environment on older adults’ walking: Literature review”, Housing and Society, No. 44(1-2), p. 141-155 [online). On the other hand, those places usually have a higher population and activity density, which tend to be super-spreaders (i.e., places with strong capabilities of spreading diseases) as well as super-susceptibles (i.e., risker places for contagion) (Chin & Bouffanais, 2020[78]Op. cit.). This means that planning and design strategies have to consider both pandemics preparedness and long-term outcomes to manage crowds and strike a balance between population health and urban vibrancy. Flexible and temporary strategies could also be taken to control the population and activity density at urban hotspots.

The outbreak of COVID-19 is a great opportunity to rethink cities to be healthier, more resilient, and sustainable. For example, Barbarossa (2020[79]Op. cit.) identified some key principles in designing streets and public spaces for post-pandemic cities, such as supporting public health guidance such as social distancing, increasing outdoor space for people, creating safer streets that prioritise public and active transport, and supporting local economies. Although densely populated cities tend to face more challenges during pandemics, this article uses Singapore’s public housing estates to illustrate the benefits of the high-rise, high-density environment in responding to COVID-19. Meanwhile, the trend of Singapore’s public housing development needs to be carefully considered to make it more conducive to population health and wellbeing and resilient to future public health crises.

[1] Barbarossa L. (2020). The post pandemic city: Challenges and opportunities for a non-motorized urban environment. An overview of Italian cases, Sustainability, No.12(17), Art. 7172 [online].

[2] Honey-Rosés J, Anguelovski I, Chireh V et al. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on public space: An early review of the emerging questions – design, perceptions and inequities, Cities & Health, No.1-17 [online].

[3] Sharifi A, Khavarian-Garmsir AR. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management, Science of the Total Environment, No.749, 142391 [online].

[4] Department of Statistics. (2021). Population trends 2021. Singapore: Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry [online].

[5] “What you can and cannot do during the circuit breaker period” [online].

[6] “Updates On Local Situation and Maintaining the Stabilisation Measures” [online].

[7] Op. cit.

[8] Ng E. (Ed.). (2009). Designing high-density cities for social and environmental sustainability, London, Earthscan.

[9] Op. cit.

[10] Johns Hopkins Coronavirus resource center, Mortality analysis [online].

[11] Tan TK, Tong LC, An TS, Cheong LW, Kwok K. (1985). Physical planning and design, In Wong AK & Yeh SH (Eds.), Housing a nation: 25 years of public housing in Singapore (pp. 56-112), Maruzen Asia for HDB.

[12] Liu TK. (1975). Design for better living conditions. In Yeh SH (Ed.), Public housing in Singapore: A multi-disciplinary study (pp. 117-184), Singapore, Singapore University Press.

[13] Fernandez W. (2011). Our homes: 50 years of housing a nation, Singapore, Straits Times Press.

[14] Op. cit.

[15] Op. cit.

[16] Hee L. (2017). Constructing Singapore public space, Singapore, Springer [DOI].

[17] Op. cit.

[18] Pozoukidou G, Chatziyiannaki Z. (2021). 15‐minute city: Decomposing the new urban planning Eutopia, Sustainability, No.13(2), Art. 928 [online].

[19] Op. cit.

[20] Heng CK, Fung JC, Cho IS, Malone-Lee LC. (2020). 未来高密度居住区规划与设计框架研究. 规划师, No.36(21), pp. 35-44 [online].

[21] Op. cit.

[22] Housing & Development Board, Health District Queenstown [online].

[23] Sun H. (2013). “Social effects of the provision and distribution of daily service shops in HDB new town in Singapore – Using case studies of Bedok, Jurong East, Bishan, Sengkang and Punggol new towns”, Master thesis, National University of Singapore.

[24] Heng CK, Yeo SJ. (2017). Singapore chronicles: Urban planning, Singapore, Institute of Policy Studies and Straits Times Press.

[25] Hong S, Choi SH. (2021). “The urban characteristics of high economic resilient neighborhoods during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case of Suwon, South Korea”, Sustainability, No. 13(9), Article 4679 [online].

[26] Mouratidis K, Yiannakou A. (2021). “COVID-19 and urban planning: Built environment, health, and well-being in Greek cities before and during the pandemic”, Cities, No. 121, Art. 103491 [online].

[27] Chang N, Yong M. (2020, February 14). Public Health Preparedness Clinics reactivated to reduce risk of COVID-19 spread, Channel NewsAsia [online].

[28] Op. cit.

[29] Chia O. (2021, July 29). “Mandatory Covid-19 testing for residents of 2 HDB blocks in Choa Chu Kang and Jurong West”, The Straits Times [online].

[30] Op. cit.

[31] Lu Y, Zhao J, Wu X, Lo SM. (2021). “Escaping to nature during a pandemic: A natural experiment in Asian cities during the COVID-19 pandemic with big social media data”, Science of the Total Environment, No. 777, Art. 146092 [online].

[32] Op. cit.

[33] Olszewska-Guizzo A, Fogel A, Escoffier N, Ho R. (2021). “Effects of COVID-19-related stay-at-home order on neuropsychophysiological response to urban spaces: Beneficial role of exposure to nature?”, Journal of Environmental Psychology, No. 75, Art. 101590 [online].

[34] Wortzel JD, Wiebe DJ, DiDomenico GE, Visoki E et al. (2021). “Association between urban greenspace and mental wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic in a U.S. cohort”, Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, No. 3 [online].

[35] Lee AC, Jordan HC, Horsley J. (2015). “Value of urban green spaces in promoting healthy living and wellbeing: Prospects for planning”, Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, No. 8, p. 131-137 [online].

[36] Cf. Green Plan, Key focus areas [online].

[37] Op. cit.

[38] Teng P. (2020). “Assuring food security in Singapore, a small island state facing COVID-19”, Food Security, No. 12(4), p. 801-804 [online].

[39] Lovell R, Husk K, Bethel A, Garside R. (2014). “What are the health and well-being impacts of community gardening for adults and children: A mixed method systematic review protocol”, Environmental Evidence, No. 3(1), p. 20 [online].

[40] Francis J, Giles-Corti B, Wood L, Knuiman M. (2012). “Creating sense of community: The role of public space”, Journal of Environmental Psychology, No. 32(4), p. 401-409 [online].

[41] Op. cit.

[42] Pai N, Vella SL. (2021). “COVID-19 and loneliness: A rapid systematic review”, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, No. 55(12), p. 1144-1156 [online].

[43] Askarizad R, He J. (2022). “Post-pandemic urban design: The equilibrium between social distancing and social interactions within the built environment”, Cities, No. 124, Art. 103618 [online].

[44] Op. cit.

[45] Centre for Liveable Cities. (2021). Singapore’s COVID-19 response and rethinking the new urban normal: A commentary. Singapore: Centre for Liveable Cities [online].

[46] Op. cit.

[47] Op. cit.

[48] Op. cit.

[49] Bracarense LD, Oliveira RL. (2021). “Access to urban activities during the Covid-19 pandemic and impacts on urban mobility: The Brazilian context”, Transport Policy, No. 110, p. 98-111 [online].

[50] Land Transport Authority. Land Transport Master Plan 2040. Singapore: Land Transport Authority [online].

[51] Op. cit.

[52] Nikitas A, Tsigdinos S, Karolemeas C, Kourmpa E, Bakogiannis E. (2021). “Cycling in the era of covid-19: Lessons learnt and best practice policy recommendations for a more bike-centric future”, Sustainability, No. 13(9), Art. 4620 [online].

[53] Land Transport Authority, “Cycling” [online].

[54] Op. cit.

[55] Foo ST. (2021, June 24). “Reimagining the workspace of tomorrow”, The Business Times [online].

[56] Wong JC, Tan J, Lim YX et al. (2021). “Non-intrusive wastewater surveillance for monitoring of a residential building for COVID-19 cases”, Science of the Total Environment, No. 786, Art. 147419 [online].

[57] Ng KG. (2021, July 8). “S’pore to double Covid-19 wastewater testing surveillance sites by 2022 from current 200”, The Straits Times [online].

[58] Lau JM, Teh PS, Toh W. (2010). “HDB’s next generation of eco-districts at Punggol and eco-modernisation of existing towns”, The IES Journal Part A: Civil & Structural Engineering, No. 3(3), p. 203-209 [online].

[59] Op. cit.

[60] “Return to Phase 2 (Heightened Alert) Measures” [online].

[61] “Updates on Phase 3 (Heightened Alert) Measures” [online].

[62] Li X. (2021, September 26). “Are certain neighbourhoods more prone to being struck by Covid-19?”, The Straits Times [online].

[63] Liu V, Diman H, Lim J. (2020, March 22). “Coronavirus: Social distancing starts – from malls to supermarkets”, The Straits Times [online].

[64] Toh TW. (2021, May 14). “Possible to keep public transport ‘very safe’ with Covid-19 precautions: Ong Ye Kung”, The Straits Times [online].

[65] Bitterman A, Hess DB. (2021). “Going dark: The post-pandemic transformation of the metropolitan retail landscape”, Town Planning Review, No. 92(3), p. 385-393 [online].

[66] Ahmed S, Sanghvi K, Yeo D. (2020). “Telemedicine takes centre stage during COVID-19 pandemic”, BMJ Innovations, No. 6(4), p. 252 [online].

[67] Tan C. (2021, September 30). “S’pore GPs stepping up to provide telemedicine care for Covid-19 patients on home recovery”, The Straits Times [online].

[68] This website is no longer available [Editor’s note].

[69] This website is no longer available [Editor’s note].

[70] Nanda A. (2021, October 9). “Seniors stuck at home, caught between loneliness and fear of Covid-19”, The Straits Times [online].

[71] Yip W, Ge L, Ho AH, Heng BH, Tan WS. (2021). “Building community resilience beyond COVID-19: The Singapore way”, The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, No. 7, Art. 100091 [online].

[72] Chin WC, Bouffanais R. (2020). “Spatial super-spreaders and super-susceptibles in human movement networks”, Sci Rep, No. 10(1), Art. 18642 [online].

[73] Leong CH, Chin WC, Feng CC, Wang YC. (2021). “A socio-ecological perspective on COVID-19 spatiotemporal integrated vulnerability in Singapore”. In Shaw SL, Sui D (Eds.), Mapping COVID-19 in space and time: Understanding the spatial and temporal dynamics of a global pandemic, Springer International Publishing, p. 81-111.

[74] Op. cit.

[75] Op. cit.

[76] Wade L. (2020). “An unequal blow”, Science, No. 368(6492), p. 700-703 [online].

[77] Hwang E. (2017). “Impacts of objective neighborhood built environment on older adults’ walking: Literature review”, Housing and Society, No. 44(1-2), p. 141-155 [online].

[78] Op. cit.

[79] Op. cit.